22 December was Army Day, a major day in socialist Yugoslavia’s calendar. It commemorated the day when in 1941 the first Proletarian Brigade was formed of the People’s Liberation Movement, which following its victory in the People’s Liberation War (as what World War II within Yugoslavia was referred to) transformed into the Jugoslovenska Narodna Armija (JNA) i.e. Yugoslav People’s Army.

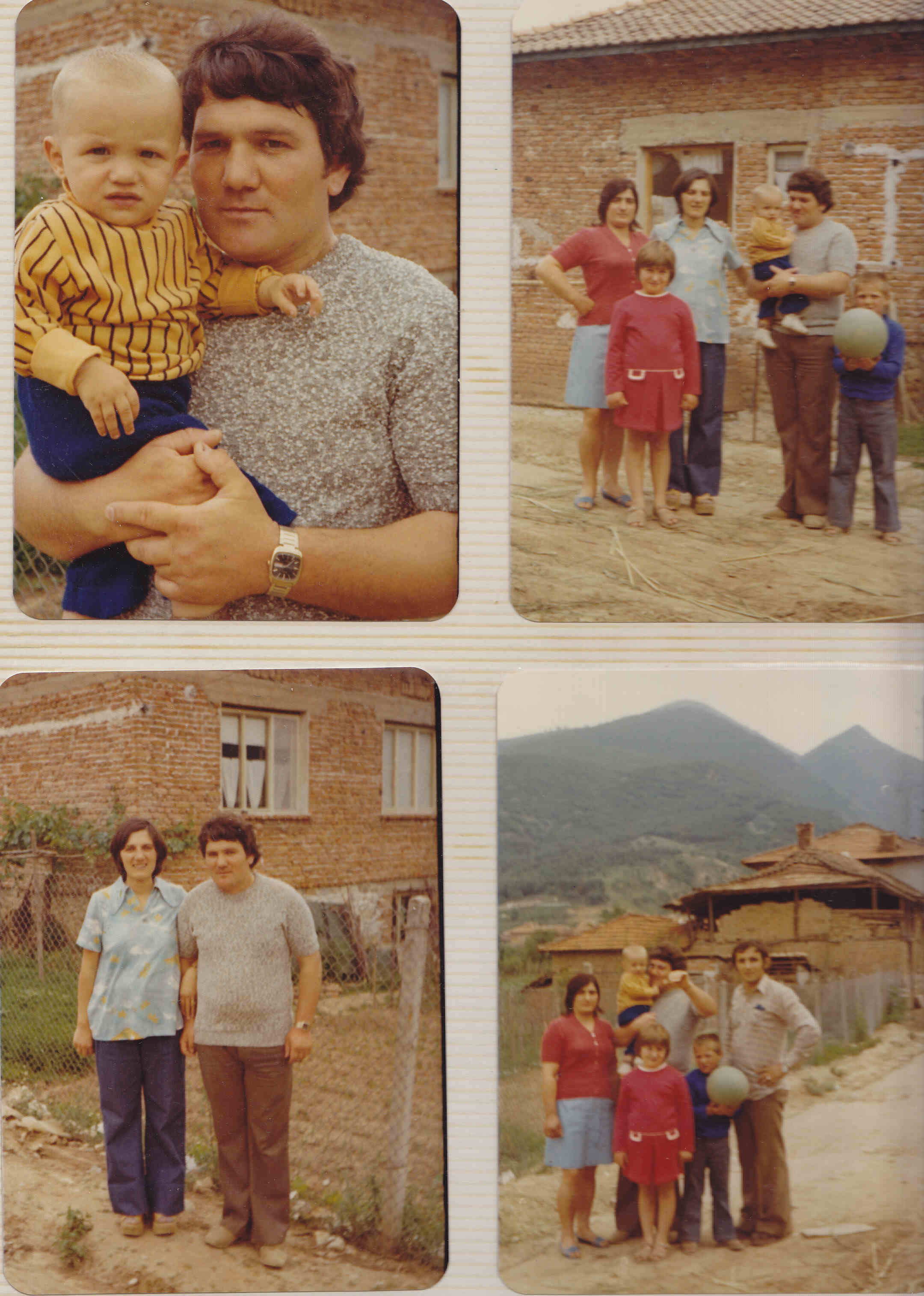

As someone whose father had served in the Yugoslav People’s Army, and so too most of my father’s friends, somewhat despite having spent my childhood far away from Yugoslavia in Australia I still was constantly exposed to so many transformative, life-changing and (seemingly) universally positive stories associated with the (up to) two years’ service in the JNA. It sounded like so much fun! This was an experience I shared with many millions of Yugoslavs who too had been regaled with stories of such happy experiences from fathers, uncles, cousins, grandfathers. Though female family members would also hear them, these stories though did appear mainly targeted at male children in what can be described as a way to build up a sense an excitement and courage for the inevitable when they too would be called up like their male ancestors and serve in the JNA. Military service in socialist Yugoslavia then had the image of something to look forward to and not feared (as it would later turn out). Culminating in this positive reinforcement was the (now obsolete) tradition of the ispraćaj u vojsku (lit. “send-off to the army”), the big celebration, akin to weddings, to send off an upcoming conscript (or conscripts) to the JNA, establishing the importance and positive connotations of this (former) rite of passage.

The military played a key role in the everyday life of Yugoslavia. Its presence was prominent but not intrusive. This manifested whether it was regularly seeing young conscripts in uniform on the streets (like in this Ceca clip filmed in the centre of Belgrade in 1989) and clogging (and smoking in) the corridors of trains, to the military-related imagery that would pop up in schoolbooks and magazines, or the long but perfectly coordinated convoys of military vehicles on roads. One of the primary Yugoslav slogans was Narod, Partija, Omladina, Armija (The people, the [Communist] Party, Youth, the Army) – the four pillars of Yugoslav society, and heard here in the song Tito je naše sunce (Tito is our sun). Hey, even I as part of the celebrations for Ilinden, Macedonia’s National Day, in the 1980s was dressed up in a WWII partisan (well, more like a JNA uniform) and with great gusto recited a poem saying how my greatest wish was to be like my “older brother” (I don’t have one) and become a soldier. By the way, this wasn’t in Yugoslavia but at the Macedonian Hall in the western suburbs of Adelaide, Australia.

When I found out that Ljubljana-based linguist and an anthropologist Tanja Petrović was to present her book Utopia of the Uniform: Affective Afterlives of the Yugoslav People’s Army at the School of Slavonic and Eastern European Studies (SSEES) at University College London (UCL) covering the afterlives of those who served in the JNA, I simply had to go. As I was to find out, the experience for millions of Yugoslav men serving in their People’s Army was life-changing not just for them but also for their descendants, including me.

Here are some personal points related to the book and the JNA in general.

Personal pilgrimages to Karlovac

Pilgrimage was a subject in the book, as with the example of the former JNA recruit who took his bewildered French wife to Žabljak, Montenegro, the place where he had served. My father served in the JNA for two years in the late 1960s in Karlovac, Croatia. My father’s main story is that the JNA taught him to eat. He’d been a picky eater, so when when he was served food on his first two days at the base, he ate nothing. But on the third day he ate everything as he was too hungry. The stories of his time made Karlovac almost legendary, sparking my interest – the city was on top of my bucket list for years. And so I did in February 2013, when I took a train no different from the one that father would have taken in the late 1960s, to see the place. Finding the barracks was a simple task as it was still a base, just now for the Croatian Army. I have since been to Karlovac another two times, with the city covered in snow two out of the three times. Before I mentioned the Karlovac pilgrimages at the book launch, panellist Professor Elena Stavreska had noted how the places where our fathers, grandfathers, brothers and cousins served were interwoven into the personal geographies of our families, gaining a somewhat mythical status. Everyone present then before asking a question or comment would first mention the place(s) that their male ancestors (or themselves) had served in the JNA, proving Stavreska’s point. By the way, the base in Karlovac no longer exists. The last time I was there was in November 2017, the barracks were unguarded and wide open to the elements in preparation for their complete demolition. I took a whole series of photos of what was left of the base and sent them off to my father.

Interestingly, I found out that other people who served in Karlovac was Tanja Petrović’s father and famous Slovenian philosopher and commentator Slavoj Žižek – though not all at the same time.

A gde si služio?

This is the first question still asked among Yugoslav men of a certain age when meeting – it means “So where did you serve?” I’d always hear my father ask this whenever he’d meet other Yugoslav men around his age. It was like a switch; this would trigger my father to start speaking in good Serbo-Croatian, the sole standard language of command in the JNA. And this would always prompt hours of joyous conversation and, at times, outrageous stories of young guys being young guys. As a child listening in to these stories, it seemed that all these former conscripts knew the nicknames of every guy who was serving at the time in a 50km radius from their base. And despite, or in spite of, the wars of the 1990s that forced alternative official outlooks towards the JNA and socialist Yugoslavia, and entrenched division over cohesion, bringing up this question amongst these men still transcends all – it’s something they have in common. I witnessed this one time on a bus in going from Dubrovnik, Croatia to Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina in 2012: a Serb and a Croat bonded by talking about their shared youth experience of being in the JNA. This was prompted when crossing the border three times – the moan everyone gave when the conductor asked us all to get our passports ready as these borders are the most visible and annoying aspects of this imposed division where before there was none. As it happened, these two men had served in the JNA at same area at the same time. Men who have been forced in recent decades to be foes were once again brothers.

Always happy times?

While serving in the JNA was officially portrayed to be a honourable experience, this was further energised through by the overwhelming positive nature of the stories said about the times most Yugoslav men had during their service. However, this positivity was not shared by all, but rarely, if ever, were these negative experiences ever aired, resulting in serious issues, social and mental, being left unresolved for decades. The first “negative” JNA experience I heard was from one Serbian Roma contemporary of my father’s, who said that his time in the Yugoslav Navy was basically spent pealing potatoes on an isolated island in the middle of the Adriatic Sea. I use scare marks on “negative” as this man would laugh it off in a “let bygones be bygones” way, while hinting that this was a common experience for Roma men in Yugoslavia where despite official policy anti-Roma racism still persisted. It can also be attributed to a defeated yet inherent acceptance of what was to be expected for such a visible and historically persecuted minority. However, it wasn’t until recently that I observed first-hand how traumatic serving in the JNA could be for some. My father’s cousin did his JNA service in the early 1980s in Kosovo – a time of great unrest in the province and where conscripts were involved in policing the Albanian-majority population. Never did he talk of any positive stories of his time in the JNA – when asked the usual question, just by responding he served in Kosovo was the cue to everyone not to delve more into things. Though he has never told us details about his time in the JNA (we have a culture of silence about these things), we do know that it was that horrific that it has manifested in much-delayed post-traumatic stress disorder in the form of chronic depression. Essentially, if you didn’t fit with the accepted discourse and culture, you then were forced to suffer in silence. My father’s cousin has since being received professional help in what has been a bold move in a society that until recently refused to acknowledge mental health issues. As what my auntie so defiantly said once when I was with her visiting my father’s, and her, cousin: “mental health issues are nothing to be ashamed of”. Since then, I’ve heard of experiences of other negative experiences by other former JNA recruits, raging from gay men who faced intense homophobia that heightened masculinity environments such as army barracks fuel to others who had to disrupt their studies or work only to face being in an environment where their skills or intellect were undervalued or scorned.

JNA and celebrities

By law, all men in Yugoslavia were to serve in the JNA. That included celebrities. The most significant of these was when Yugoslav pop megastar and teen idol Zdravko Čolić finally did his JNA service in 1978-9. Of course, it was a major propaganda event. Hundreds of his adoring female fans crowded the platform at Sarajevo railway station to send him off to the army. You could say this was the Yugoslav equivalent to Elvis Presley and his military service. Another positive celebrity link to serving in the JNA was when in 1996 legendary Yugoslav Neo-Folk star Šaban Šaulić recorded two modern versions of Macedonian folk songs. People at the time were wondering why Šaulić, born in Serbia to Bosniak parents, would do this? As he revealed, he did this in homage for the time he served in the JNA in Bitola, Macedonia.

The “School of Brotherhood and Unity” at odds

Great points in the book about how the very centralised, regimented and monolingual, and therefore monocultural, structure and nature of the JNA were the antithesis of those of the WW2 partisan brigades from which the JNA derived and based its pre-1990 legitimacy as a protector of the Yugoslav people, as well as the decentralised, multilingual, self-managed, non-aligned, multicultural nature and structure of socialist Yugoslavia as a whole. Petrović also highlighted how having an army of conscripts, many of whom were with limited skills and deliberately sent to places within Yugoslavia far from their birthplaces, was hardly the most efficient or effective basis for the defence force of Yugoslavia. However, the primarily effective role of the JNA was as it was commonly referred to: being the school of Brotherhood and Unity (Yugoslavia’s motto).

Parallels with the role of the military and military service in other countries

I’ve heard of similar experiences with men from the former USSR, such as a taxi driver I met in Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky in far eastern Russia in 2017, who even though was originally from cosmopolitan Kyiv, Ukraine, he enjoyed his first taste of freedom away from his family in this isolated place and chose to remain there. The biggest parallels are with Israel, where despite the small size of the country and due to grounding policies that saw enforced segregation, its various social groups (secular Ashkenazim, Mizrahim, Russian-speakers, Haredim, Druze, etc.) don’t interact as much as it would seem. So the IDF forces the recruits together, much like how the JNA deliberately mixed its recruits from all parts of the federation and of different socio-economic and ethnic groups. Much as the JNA was popularly billed as “the School of Brotherhood and Unity”, the IDF in Israel is referred to as “the melting pot of Israel”.

Coming to terms with a poisoned legacy

Coming from that parallel is the aftermath of the 1990s war and the changed perception of the JNA from an element of the people to one against the people and its involvement in the atrocities of the 1990s. By the time the JNA was practically sending boys to be killed in the meat grinder that was the front line in Srem (Syrmia) centred in Vukovar in 1991 (much like they did in the bloody battle on the Syrmian Front in early 1945). With Yugoslavia, and particularly the JNA, having descended into Milosevic-orchestrated Serb domination (half-joking referred to as “Serboslavia”), rather than send their boys in celebrations, people particularly in non-Serb parts of Yugoslavia were massively and collectively involved in hiding them. This was the case with one of my first cousins.

Now we have former recruits coming to terms that the Army they once served in and believed to be a side of good later became a tainted force associated with war crimes – something some Israelis are now facing with their legacy of having served in the IDF.

Lastly, here’s the red star badge that was on my father’s Titovka (Partisan hat) as part of his JNA uniform. It stares at me next to my workspace. It was also an item I presented at this talk earlier this year also at UCL SSEES. It’s a constant reminder of a symbol of my childhood and formative years, in good and in bad, in brotherhood and unity.

Utopia of the Uniform: Affective Afterlives of the Yugoslav People’s Army is available for purchase from Duke University Press.

.%20A%20day%20of%20campaigning%20%E2%99%80%20%E2%80%A6%20or%20a%20day%20to%20buy%20flowers%20%F0%9F%92%90.jpg)